The remote server returned an unexpected response: (400) Bad Request.

The remote server returned an unexpected response: (400) Bad Request.

Hilbert’s fifth problem asks to clarify the extent that the assumption on a differentiable or smooth structure is actually needed in the theory of Lie groups and their actions. While this question is not precisely formulated and is thus open to some interpretation, the following result of Gleason and Montgomery-Zippin answers at least one aspect of this question:

Theorem 1 (Hilbert’s fifth problem) Let  be a topological group which is locally Euclidean (i.e. it is a topological manifold). Then

be a topological group which is locally Euclidean (i.e. it is a topological manifold). Then  is isomorphic to a Lie group.

is isomorphic to a Lie group.

Theorem 1 can be viewed as an application of the more general structural theory of locally compact groups. In particular, Theorem 1 can be deduced from the following structural theorem of Gleason and Yamabe:

Theorem 2 (Gleason-Yamabe theorem) Let  be a locally compact group, and let

be a locally compact group, and let  be an open neighbourhood of the identity in

be an open neighbourhood of the identity in  . Then there exists an open subgroup

. Then there exists an open subgroup  of

of  , and a compact subgroup

, and a compact subgroup  of

of  contained in

contained in  , such that

, such that  is isomorphic to a Lie group.

is isomorphic to a Lie group.

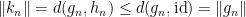

The deduction of Theorem 1 from Theorem 2 proceeds using the Brouwer invariance of domain theorem and is discussed in this previous post. In this post, I would like to discuss the proof of Theorem 2. We can split this proof into three parts, by introducing two additional concepts. The first is the property of having no small subgroups:

Definition 3 (NSS) A topological group  is said to have no small subgroups, or is NSS for short, if there is an open neighbourhood

is said to have no small subgroups, or is NSS for short, if there is an open neighbourhood  of the identity in

of the identity in  that contains no subgroups of

that contains no subgroups of  other than the trivial subgroup

other than the trivial subgroup  .

.

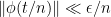

An equivalent definition of an NSS group is one which has an open neighbourhood  of the identity that every non-identity element

of the identity that every non-identity element  escapes in finite time, in the sense that

escapes in finite time, in the sense that  for some positive integer

for some positive integer  . It is easy to see that all Lie groups are NSS; we shall shortly see that the converse statement (in the locally compact case) is also true, though significantly harder to prove.

. It is easy to see that all Lie groups are NSS; we shall shortly see that the converse statement (in the locally compact case) is also true, though significantly harder to prove.

Another useful property is that of having what I will call a Gleason metric:

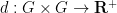

Definition 4 Let  be a topological group. A Gleason metric on

be a topological group. A Gleason metric on  is a left-invariant metric

is a left-invariant metric  which generates the topology on

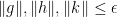

which generates the topology on  and obeys the following properties for some constant

and obeys the following properties for some constant  , writing

, writing  for

for  :

:

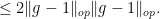

For instance, the unitary group  with the operator norm metric

with the operator norm metric  can easily verified to be a Gleason metric, with the commutator estimate (1) coming from the inequality

can easily verified to be a Gleason metric, with the commutator estimate (1) coming from the inequality

![\displaystyle \| [g,h] - 1 \|_{op} = \| gh - hg \|_{op} \displaystyle \| [g,h] - 1 \|_{op} = \| gh - hg \|_{op}](http://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5Cdisplaystyle++%5C%7C+%5Bg%2Ch%5D+-+1+%5C%7C_%7Bop%7D+%3D+%5C%7C+gh+-+hg+%5C%7C_%7Bop%7D&bg=ffffff&fg=000000&s=0)

Similarly, any left-invariant Riemannian metric on a (connected) Lie group can be verified to be a Gleason metric. From the escape property one easily sees that all groups with Gleason metrics are NSS; again, we shall see that there is a partial converse.

Remark 1 The escape and commutator properties are meant to capture “Euclidean-like” structure of the group. Other metrics, such as Carnot-Carathéodory metrics on Carnot Lie groups such as the Heisenberg group, usually fail one or both of these properties.

The proof of Theorem 2 can then be split into three subtheorems:

Theorem 5 (Reduction to the NSS case) Let  be a locally compact group, and let

be a locally compact group, and let  be an open neighbourhood of the identity in

be an open neighbourhood of the identity in  . Then there exists an open subgroup

. Then there exists an open subgroup  of

of  , and a compact subgroup

, and a compact subgroup  of

of  contained in

contained in  , such that

, such that  is NSS, locally compact, and metrisable.

is NSS, locally compact, and metrisable.

Theorem 6 (Gleason’s lemma) Let  be a locally compact metrisable NSS group. Then

be a locally compact metrisable NSS group. Then  has a Gleason metric.

has a Gleason metric.

Theorem 7 (Building a Lie structure) Let  be a locally compact group with a Gleason metric. Then

be a locally compact group with a Gleason metric. Then  is isomorphic to a Lie group.

is isomorphic to a Lie group.

Clearly, by combining Theorem 5, Theorem 6, and Theorem 7 one obtains Theorem 2 (and hence Theorem 1).

Theorem 5 and Theorem 6 proceed by some elementary combinatorial analysis, together with the use of Haar measure (to build convolutions, and thence to build “smooth” bump functions with which to create a metric, in a variant of the analysis used to prove the Birkhoff-Kakutani theorem); Theorem 5 also requires Peter-Weyl theorem (to dispose of certain compact subgroups that arise en route to the reduction to the NSS case), which was discussed previously on this blog.

In this post I would like to detail the final component to the proof of Theorem 2, namely Theorem 7. (I plan to discuss the other two steps, Theorem 5 and Theorem 6, in a separate post.) The strategy is similar to that used to prove von Neumann’s theorem, as discussed in this previous post (and von Neumann’s theorem is also used in the proof), but with the Gleason metric serving as a substitute for the faithful linear representation. Namely, one first gives the space  of one-parameter subgroups of

of one-parameter subgroups of  enough of a structure that it can serve as a proxy for the “Lie algebra” of

enough of a structure that it can serve as a proxy for the “Lie algebra” of  ; specifically, it needs to be a vector space, and the “exponential map” needs to cover an open neighbourhood of the identity. This is enough to set up an “adjoint” representation of

; specifically, it needs to be a vector space, and the “exponential map” needs to cover an open neighbourhood of the identity. This is enough to set up an “adjoint” representation of  , whose image is a Lie group by von Neumann’s theorem; the kernel is essentially the centre of

, whose image is a Lie group by von Neumann’s theorem; the kernel is essentially the centre of  , which is abelian and can also be shown to be a Lie group by a similar analysis. To finish the job one needs to use arguments of Kuranishi and of Gleason, as discussed in this previous post.

, which is abelian and can also be shown to be a Lie group by a similar analysis. To finish the job one needs to use arguments of Kuranishi and of Gleason, as discussed in this previous post.

The arguments here can be phrased either in the standard analysis setting (using sequences, and passing to subsequences often) or in the nonstandard analysis setting (selecting an ultrafilter, and then working with infinitesimals). In my view, the two approaches have roughly the same level of complexity in this case, and I have elected for the standard analysis approach.

Remark 2 From Theorem 7 we see that a Gleason metric structure is a good enough substitute for smooth structure that it can actually be used to reconstruct the entire smooth structure; roughly speaking, the commutator estimate (1) allows for enough “Taylor expansion” of expressions such as  that one can simulate the fundamentals of Lie theory (in particular, construction of the Lie algebra and the exponential map, and its basic properties. The advantage of working with a Gleason metric rather than a smoother structure, though, is that it is relatively undemanding with regards to regularity; in particular, the commutator estimate (1) is roughly comparable to the imposition

that one can simulate the fundamentals of Lie theory (in particular, construction of the Lie algebra and the exponential map, and its basic properties. The advantage of working with a Gleason metric rather than a smoother structure, though, is that it is relatively undemanding with regards to regularity; in particular, the commutator estimate (1) is roughly comparable to the imposition  structure on the group

structure on the group  , as this is the minimal regularity to get the type of Taylor approximation (with quadratic errors) that would be needed to obtain a bound of the form (1). We will return to this point in a later post.

, as this is the minimal regularity to get the type of Taylor approximation (with quadratic errors) that would be needed to obtain a bound of the form (1). We will return to this point in a later post.

— 1. Proof of theorem — We now prove Theorem 7. Henceforth,  is a locally compact group with a Gleason metric

is a locally compact group with a Gleason metric  (and an associated “norm”

(and an associated “norm”  ). In particular, by the Heine-Borel theorem,

). In particular, by the Heine-Borel theorem,  is complete with this metric.

is complete with this metric.

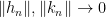

We use the asymptotic notation  in place of

in place of  for some constant

for some constant  that can vary from line to line (in particular,

that can vary from line to line (in particular,  need not be the constant appearing in the definition of a Gleason metric), and write

need not be the constant appearing in the definition of a Gleason metric), and write  for

for  . We also let

. We also let  be a sufficiently small constant (depending only on the constant in the definition of a Gleason metric) to be chosen later.

be a sufficiently small constant (depending only on the constant in the definition of a Gleason metric) to be chosen later.

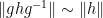

Note that the left-invariant metric properties of  give the symmetry property

give the symmetry property

and the triangle inequality

From the commutator estimate (1) and the triangle inequality we also obtain a conjugation estimate

whenever  . Since left-invariance gives

. Since left-invariance gives

we then conclude an approximate right invariance

whenever  . In a similar spirit, the commutator estimate (1) also gives

. In a similar spirit, the commutator estimate (1) also gives

whenever  .

.

This has the following useful consequence, which asserts that the power maps  behave like dilations:

behave like dilations:

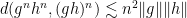

Lemma 8 If  and

and  , then

, then

and

Proof: We begin with the first inequality. By the triangle inequality, it suffices to show that

uniformly for all ![{0 \leq i . By left-invariance and approximate right-invariance, the left-hand side is comparable to </P><IMG class=latex title=]()

which by (2) is bounded above by

as required.

Now we prove the second estimate. Write  , then

, then  . We have

. We have

thanks to the escape property (shrinking  if necessary). On the other hand, from the first inequality, we have

if necessary). On the other hand, from the first inequality, we have

If  is small enough, the claim now follows from the triangle inequality.

is small enough, the claim now follows from the triangle inequality.

Remark 3 Lemma 8 implies (by a standard covering argument) that the group  is locally of bounded doubling, though we will not use this fact here.

is locally of bounded doubling, though we will not use this fact here.

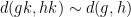

Now we introduce the space  of one-parameter subgroups, i.e. continuous homomorphisms

of one-parameter subgroups, i.e. continuous homomorphisms  . We give this space the compact-open topology, thus the topology is generated by balls of the form

. We give this space the compact-open topology, thus the topology is generated by balls of the form

![\displaystyle \{ \phi \in L(G): \sup_{t \in I} d(\phi(t),\phi_0(t)) </P><P>for <IMG class=latex title=]()

,

, and compact

. Actually, using the homomorphism property, one can use a single compact interval

, such as

![{[-1,1]} {[-1,1]}](http://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%7B%5B-1%2C1%5D%7D&bg=ffffff&fg=000000&s=0)

, to generate the topology if desired, thus making

a metric space.

Given that  is eventually going to be shown to be a Lie group,

is eventually going to be shown to be a Lie group,  must be isomorphic to a Euclidean space. We now move towards this goal by establishing various properties of

must be isomorphic to a Euclidean space. We now move towards this goal by establishing various properties of  that Euclidean spaces enjoy.

that Euclidean spaces enjoy.

Lemma 9  is locally compact.

is locally compact.

Proof: It is easy to see that  is complete. Let

is complete. Let  . As

. As  is continuous, we can find an interval

is continuous, we can find an interval ![{I = [-T,T]} {I = [-T,T]}](http://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%7BI+%3D+%5B-T%2CT%5D%7D&bg=ffffff&fg=000000&s=0) small enough that

small enough that  for all

for all ![{t \in [-T,T]} {t \in [-T,T]}](http://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%7Bt+%5Cin+%5B-T%2CT%5D%7D&bg=ffffff&fg=000000&s=0) . By the Heine-Borel theorem, it will suffice to show that the set

. By the Heine-Borel theorem, it will suffice to show that the set

![\displaystyle B := \{ \phi \in L(G): \sup_{t \in [-T,T]} d(\phi(t),\phi_0(t)) </P><P>is totally bounded. By the Arzelá-Ascoli theorem, it suffices to show that the family of functions in <IMG class=latex title={B} alt={B} src=]()

is equicontinuous.

By construction, we have  whenever

whenever  . By the escape property, this implies (for

. By the escape property, this implies (for  small enough, of course) that

small enough, of course) that  for all

for all  and

and  , thus

, thus  whenever

whenever  . From the homomorphism property, we conclude that

. From the homomorphism property, we conclude that  whenever

whenever  , which gives uniform Lipschitz control and hence equicontinuity as desired.

, which gives uniform Lipschitz control and hence equicontinuity as desired.

We observe for future reference that the proof of the above lemma also shows that all one-parameter subgroups are locally Lipschitz.

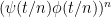

Now we put a vector space structure on  , which we define by analogy with the Lie group case, in which each tangent vector

, which we define by analogy with the Lie group case, in which each tangent vector  generates a one-parameter subgroup

generates a one-parameter subgroup  . From this analogy, the scalar multiplication operation has an obvious definition: if

. From this analogy, the scalar multiplication operation has an obvious definition: if  and

and  , we define

, we define  to be the one-parameter subgroup

to be the one-parameter subgroup

which is easily seen to actually be a one-parameter subgroup.

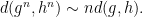

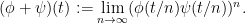

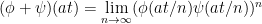

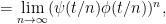

Now we turn to the addition operation. In the Lie group case, one can express the one-parameter subgroup  in terms of the one-parameter subgroups

in terms of the one-parameter subgroups  ,

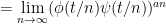

,  by the limiting formula

by the limiting formula

In view of this, we would like to define the sum  of two one-parameter subgroups

of two one-parameter subgroups  by the formula

by the formula

Lemma 10 If  , then

, then  is well-defined and also lies in

is well-defined and also lies in  .

.

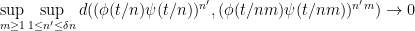

Proof: To show well-definedness, it suffices to show that for each  , the sequence

, the sequence  is a Cauchy sequence. It suffices to show that

is a Cauchy sequence. It suffices to show that

as  . By the continuity of multiplication, it suffices to show that there is some

. By the continuity of multiplication, it suffices to show that there is some  such that

such that

as  .

.

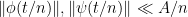

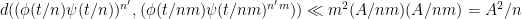

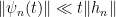

Since  are locally Lipschitz, we can find a quantity

are locally Lipschitz, we can find a quantity  (depending on

(depending on  ) such that

) such that

for all  . From Lemma 8, we conclude that

. From Lemma 8, we conclude that

if  and

and  is sufficiently large. Another application of Lemma 8 then gives

is sufficiently large. Another application of Lemma 8 then gives

if  ,

,  is sufficiently large,

is sufficiently large,  , and

, and  is sufficiently small depending on

is sufficiently small depending on  . The claim follows.

. The claim follows.

The above argument in fact shows that  is uniformly Cauchy for

is uniformly Cauchy for  in a compact interval, and so the pointwise limit

in a compact interval, and so the pointwise limit  is in fact a uniform limit of continuous functions and is thus continuous. To prove that

is in fact a uniform limit of continuous functions and is thus continuous. To prove that  is a homomorphism, it suffices by density of the rationals to show that

is a homomorphism, it suffices by density of the rationals to show that

and

for all  and all positive integers

and all positive integers  . To prove the first claim, we observe that

. To prove the first claim, we observe that

and similarly for  and

and  , whence the claim. To prove the second claim, we see that

, whence the claim. To prove the second claim, we see that

but  is

is  conjugated by

conjugated by  , which goes to the identity; and the claim follows.

, which goes to the identity; and the claim follows.

also has an obvious zero element, namely the trivial one-parameter subgroup

also has an obvious zero element, namely the trivial one-parameter subgroup  .

.

Lemma 11  is a topological vector space.

is a topological vector space.

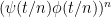

Proof: We first show that  is a vector space. It is clear that the zero element

is a vector space. It is clear that the zero element  of

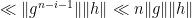

of  is an additive and scalar multiplication identity, and that scalar multiplication is associative. To show that addition is commutative, we again use the observation that

is an additive and scalar multiplication identity, and that scalar multiplication is associative. To show that addition is commutative, we again use the observation that  is

is  conjugated by an element that goes to the identity. A similar argument shows that

conjugated by an element that goes to the identity. A similar argument shows that  , and a change of variables argument shows that

, and a change of variables argument shows that  for all positive integers

for all positive integers  , hence for all rational

, hence for all rational  , and hence by continuity for all real

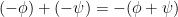

, and hence by continuity for all real  . The only remaining thing to show is that addition is associative, thus if

. The only remaining thing to show is that addition is associative, thus if  , that

, that  for all

for all  . By the homomorphism property, it suffices to show this for all sufficiently small

. By the homomorphism property, it suffices to show this for all sufficiently small  .

.

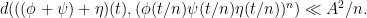

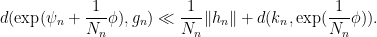

An inspection of the argument used to establish (10) reveals that there is a constant  such that

such that

for all small  and all large

and all large  , and hence also that

, and hence also that

(thanks to Lemma 8). Similarly we have (after adjusting  if necessary)

if necessary)

From Lemma 8 we have

and thus

Similarly for  . By the triangle inequality we conclude that

. By the triangle inequality we conclude that

sending  to zero, the claim follows.

to zero, the claim follows.

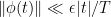

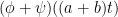

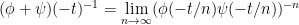

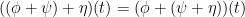

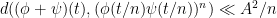

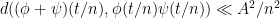

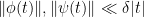

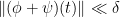

Finally, we need to show that the vector space operations are continuous. It is easy to see that scalar multiplication is continuous, as are the translation operations; the only remaining thing to verify is that addition is continuous at the origin. Thus, for every  we need to find a

we need to find a  such that

such that ![{\sup_{t \in [-1,1]} \| (\phi+\psi)(t) \| \leq \epsilon} {\sup_{t \in [-1,1]} \| (\phi+\psi)(t) \| \leq \epsilon}](http://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%7B%5Csup_%7Bt+%5Cin+%5B-1%2C1%5D%7D+%5C%7C+%28%5Cphi%2B%5Cpsi%29%28t%29+%5C%7C+%5Cleq+%5Cepsilon%7D&bg=ffffff&fg=000000&s=0) whenever

whenever ![{\sup_{t \in [-1,1]} \| \phi(t) \| \leq \delta} {\sup_{t \in [-1,1]} \| \phi(t) \| \leq \delta}](http://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%7B%5Csup_%7Bt+%5Cin+%5B-1%2C1%5D%7D+%5C%7C+%5Cphi%28t%29+%5C%7C+%5Cleq+%5Cdelta%7D&bg=ffffff&fg=000000&s=0) and

and ![{\sup_{t \in [-1,1]} \| \psi(t) \| \leq \delta} {\sup_{t \in [-1,1]} \| \psi(t) \| \leq \delta}](http://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%7B%5Csup_%7Bt+%5Cin+%5B-1%2C1%5D%7D+%5C%7C+%5Cpsi%28t%29+%5C%7C+%5Cleq+%5Cdelta%7D&bg=ffffff&fg=000000&s=0) . But if

. But if  are as above, then by the escape property (assuming

are as above, then by the escape property (assuming  small enough) we conclude that

small enough) we conclude that  for

for ![{t \in [-1,1]} {t \in [-1,1]}](http://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%7Bt+%5Cin+%5B-1%2C1%5D%7D&bg=ffffff&fg=000000&s=0) , and then from the triangle inequality we conclude that

, and then from the triangle inequality we conclude that  for

for ![{t \in [-1,1]} {t \in [-1,1]}](http://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%7Bt+%5Cin+%5B-1%2C1%5D%7D&bg=ffffff&fg=000000&s=0) , giving the claim.

, giving the claim.

As  is both locally compact, metrisable, and a topological vector space, it must be isomorphic to a finite-dimensional vector space

is both locally compact, metrisable, and a topological vector space, it must be isomorphic to a finite-dimensional vector space  with the usual topology (see this blog post for a proof).

with the usual topology (see this blog post for a proof).

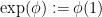

In analogy with the Lie algebra setting, we define the exponential map  by setting

by setting  . Given the topology on

. Given the topology on  , it is clear that this is a continuous map. Using Lemma 8 one can see that the exponential map is locally injective near the origin, although we will not actually need this fact.

, it is clear that this is a continuous map. Using Lemma 8 one can see that the exponential map is locally injective near the origin, although we will not actually need this fact.

We have proved a number of useful things about  , but at present we have not established that

, but at present we have not established that  is large in any substantial sense; indeed, at present,

is large in any substantial sense; indeed, at present,  could be completely trivial even if

could be completely trivial even if  was large. In particular, the image of the exponential map

was large. In particular, the image of the exponential map  could conceivably be quite small. We now address this issue. As a warmup, we show that

could conceivably be quite small. We now address this issue. As a warmup, we show that  is at least non-trivial if

is at least non-trivial if  is non-trivial:

is non-trivial:

Proposition 12 Suppose that  is not a discrete group. Then

is not a discrete group. Then  is non-trivial.

is non-trivial.

Of course, the converse is obvious; discrete groups do not admit any non-trivial one-parameter subgroups.

Proof: As  is not discrete, there is a sequence

is not discrete, there is a sequence  of non-identity elements of

of non-identity elements of  such that

such that  as

as  . Writing

. Writing  for the integer part of

for the integer part of  , then

, then  as

as  , and we conclude from the escape property that

, and we conclude from the escape property that  for all

for all  .

.

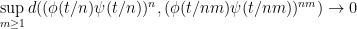

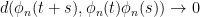

We define the approximate one-parameter subgroups ![{\phi_n: [-1,1] \rightarrow G} {\phi_n: [-1,1] \rightarrow G}](http://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%7B%5Cphi_n%3A+%5B-1%2C1%5D+%5Crightarrow+G%7D&bg=ffffff&fg=000000&s=0) by setting

by setting

Then we have  for

for  , and we have the approximate homomorphism property

, and we have the approximate homomorphism property

uniformly whenever  . As a consequence,

. As a consequence,  is asymptotically equicontinuous on

is asymptotically equicontinuous on ![{[-1,1]} {[-1,1]}](http://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%7B%5B-1%2C1%5D%7D&bg=ffffff&fg=000000&s=0) , and so by (a slight generalisation of) the Arzéla-Ascoli theorem, we may pass to a subsequence in which

, and so by (a slight generalisation of) the Arzéla-Ascoli theorem, we may pass to a subsequence in which  converges uniformly to a limit

converges uniformly to a limit ![{\phi: [-1,1] \rightarrow G} {\phi: [-1,1] \rightarrow G}](http://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%7B%5Cphi%3A+%5B-1%2C1%5D+%5Crightarrow+G%7D&bg=ffffff&fg=000000&s=0) , which is a genuine homomorphism that is genuinely continuous, and is thus can be extended to a one-parameter subgroup. Also,

, which is a genuine homomorphism that is genuinely continuous, and is thus can be extended to a one-parameter subgroup. Also,  for all

for all  , and thus

, and thus  ; in particular,

; in particular,  is non-trivial, and the claim follows.

is non-trivial, and the claim follows.

We now generalise the above proposition to a more useful result.

Proposition 13 For any neighbourhood  of the origin in

of the origin in  ,

,  is a neighbourhood of the identity in

is a neighbourhood of the identity in  .

.

Proof: We use an argument of Hirschfeld (communicated to me by van den Dries and Goldbring). By shrinking  if necessary, we may assume that

if necessary, we may assume that  is a compact star-shaped neighbourhood, with

is a compact star-shaped neighbourhood, with  contained in the ball of radius

contained in the ball of radius  around the origin. As

around the origin. As  is compact,

is compact,  is compact also.

is compact also.

Suppose for contradiction that  is not a neighbourhood of the identity, then there is a sequence

is not a neighbourhood of the identity, then there is a sequence  of elements of

of elements of  such that

such that  as

as  . By the compactness of

. By the compactness of  , we can find an element

, we can find an element  of

of  that minimises the distance

that minimises the distance  . If we then write

. If we then write  , then

, then

and hence  as

as  .

.

Let  be the integer part of

be the integer part of  , then

, then  as

as  , and

, and  for all

for all  .

.

Let ![{\phi_n: [-1,1] \rightarrow G} {\phi_n: [-1,1] \rightarrow G}](http://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%7B%5Cphi_n%3A+%5B-1%2C1%5D+%5Crightarrow+G%7D&bg=ffffff&fg=000000&s=0) be the approximate one-parameter subgroups defined as

be the approximate one-parameter subgroups defined as

As before, we may pass to a subsequence such that  converges uniformly to a limit

converges uniformly to a limit ![{\phi: [-1,1] \rightarrow G} {\phi: [-1,1] \rightarrow G}](http://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%7B%5Cphi%3A+%5B-1%2C1%5D+%5Crightarrow+G%7D&bg=ffffff&fg=000000&s=0) , which extends to a one-parameter subgroup

, which extends to a one-parameter subgroup  .

.

In a similar vein, since  , we can find

, we can find  such that

such that  , which by the escape property (and the smallness of

, which by the escape property (and the smallness of  implies that

implies that  for

for  . In particular,

. In particular,  goes to zero in

goes to zero in  .

.

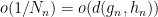

We now claim that  is close to

is close to  . Indeed, from Lemma 8 we see that

. Indeed, from Lemma 8 we see that

Since  , we conclude from the triangle inequality and left-invariance that

, we conclude from the triangle inequality and left-invariance that

But from Lemma 8 again, one has

and thus

But for  large enough,

large enough,  lies in

lies in  , and so the distance from

, and so the distance from  to

to  is

is  . But this contradicts the minimality of

. But this contradicts the minimality of  for

for  large enough, and the claim follows.

large enough, and the claim follows.

We have some easy corollaries of this result:

Corollary 14  is locally connected. In particular, the connected component

is locally connected. In particular, the connected component  of the identity is an open subgroup of

of the identity is an open subgroup of  .

.

Corollary 15 (Abelian case) If  is abelian, then

is abelian, then  is isomorphic to a Lie group. In particular, in the non-abelian setting, the centre

is isomorphic to a Lie group. In particular, in the non-abelian setting, the centre  of

of  is a Lie group.

is a Lie group.

Proof: In the abelian case one easily sees that  is a homomorphism. Thus we see from Proposition 13 that

is a homomorphism. Thus we see from Proposition 13 that  has locally the structure of a vector space, and the claim clearly follows in that case.

has locally the structure of a vector space, and the claim clearly follows in that case.

We are now finally ready to prove Theorem 7. By Corollary 14 we may assume without loss of generality that  is connected. (Note that if a topological group

is connected. (Note that if a topological group  is locally connected, and the connected component of the identity

is locally connected, and the connected component of the identity  is a Lie group, then the entire group a Lie group, because all outer automorphisms of

is a Lie group, then the entire group a Lie group, because all outer automorphisms of  are necessarily smooth, as discussed here.)

are necessarily smooth, as discussed here.)

Now we consider the adjoint action of  on

on  . If

. If  and

and  , we can define another one-parameter subgroup

, we can define another one-parameter subgroup  by setting

by setting

As conjugation by  is an automorphism, one easily verifies that

is an automorphism, one easily verifies that  is linear, thus

is linear, thus  is a map from

is a map from  to the finite-dimensional linear group

to the finite-dimensional linear group  . One easily verifies that this map is continuous, and so

. One easily verifies that this map is continuous, and so  is a finite-dimensional linear representation of

is a finite-dimensional linear representation of  . If

. If  is in the kernel of this representation, then by construction,

is in the kernel of this representation, then by construction,  centralises

centralises  , and thus by Proposition 13, centralises an open neighbourhood of the identity in

, and thus by Proposition 13, centralises an open neighbourhood of the identity in  . As we are assuming

. As we are assuming  to be connected, we conclude that

to be connected, we conclude that  is central. Thus we see that the kernel of

is central. Thus we see that the kernel of  is the center

is the center  , thus giving a short exact sequence

, thus giving a short exact sequence

The adjoint representation  is a faithful finite-dimensional linear representation of

is a faithful finite-dimensional linear representation of  , and so

, and so  is a Lie group by a theorem of von Neumann (discussed here). By Corollary 15,

is a Lie group by a theorem of von Neumann (discussed here). By Corollary 15,  is a central Lie group. By a result of Kakutani and Gleason (discussed here), this implies that

is a central Lie group. By a result of Kakutani and Gleason (discussed here), this implies that  is itself a Lie group, as required.

is itself a Lie group, as required.

Remark 4 An alternate approach to Theorem 7 would be to construct a Lie bracket on  , and then show that the multiplication law on

, and then show that the multiplication law on  is locally given by the Baker-Campbell-Hausdorff formula; we will discuss this approach in a sequel to this post.

is locally given by the Baker-Campbell-Hausdorff formula; we will discuss this approach in a sequel to this post.