The formatter threw an exception while trying to deserialize the message: Error in deserializing body of request message for operation 'Translate'. The maximum string content length quota (30720) has been exceeded while reading XML data. This quota may be increased by changing the MaxStringContentLength property on the XmlDictionaryReaderQuotas object used when creating the XML reader. Line 2, position 33673.

The formatter threw an exception while trying to deserialize the message: Error in deserializing body of request message for operation 'Translate'. The maximum string content length quota (30720) has been exceeded while reading XML data. This quota may be increased by changing the MaxStringContentLength property on the XmlDictionaryReaderQuotas object used when creating the XML reader. Line 1, position 33886.

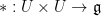

Let  be a Lie group with Lie algebra

be a Lie group with Lie algebra  . As is well known, the exponential map

. As is well known, the exponential map  is a local homeomorphism near the identity. As such, the group law on

is a local homeomorphism near the identity. As such, the group law on  can be locally pulled back to an operation

can be locally pulled back to an operation  defined on a neighbourhood

defined on a neighbourhood  of the identity in

of the identity in  , defined as

, defined as

where  is the local inverse of the exponential map. One can view

is the local inverse of the exponential map. One can view  as the group law expressed in local exponential coordinates around the origin.

as the group law expressed in local exponential coordinates around the origin.

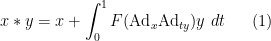

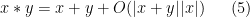

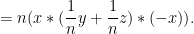

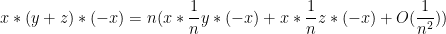

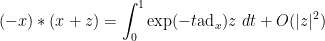

An asymptotic expansion for  is provided by the Baker-Campbell-Hausdorff (BCH) formula

is provided by the Baker-Campbell-Hausdorff (BCH) formula

![\displaystyle x*y = x+y+ \frac{1}{2} [x,y] + \frac{1}{12}[x,[x,y]] - \frac{1}{12}[y,[x,y]] + \ldots \displaystyle x*y = x+y+ \frac{1}{2} [x,y] + \frac{1}{12}[x,[x,y]] - \frac{1}{12}[y,[x,y]] + \ldots](http://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5Cdisplaystyle++x%2Ay+%3D+x%2By%2B+%5Cfrac%7B1%7D%7B2%7D+%5Bx%2Cy%5D+%2B+%5Cfrac%7B1%7D%7B12%7D%5Bx%2C%5Bx%2Cy%5D%5D+-+%5Cfrac%7B1%7D%7B12%7D%5By%2C%5Bx%2Cy%5D%5D+%2B+%5Cldots&bg=ffffff&fg=000000&s=0)

for all sufficiently small  , where

, where ![{[,]: {\mathfrak g} \times {\mathfrak g} \rightarrow {\mathfrak g}} {[,]: {\mathfrak g} \times {\mathfrak g} \rightarrow {\mathfrak g}}](http://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%7B%5B%2C%5D%3A+%7B%5Cmathfrak+g%7D+%5Ctimes+%7B%5Cmathfrak+g%7D+%5Crightarrow+%7B%5Cmathfrak+g%7D%7D&bg=ffffff&fg=000000&s=0) is the Lie bracket. More explicitly, one has the Baker-Campbell-Hausdorff-Dynkin formula

is the Lie bracket. More explicitly, one has the Baker-Campbell-Hausdorff-Dynkin formula

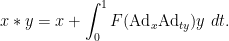

for all sufficiently small  , where

, where  ,

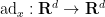

,  is the adjoint representation

is the adjoint representation ![{\hbox{ad}_x(y) := [x,y]} {\hbox{ad}_x(y) := [x,y]}](http://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%7B%5Chbox%7Bad%7D_x%28y%29+%3A%3D+%5Bx%2Cy%5D%7D&bg=ffffff&fg=000000&s=0) , and

, and  is the function

is the function

which is real analytic near  and can thus be applied to linear operators sufficiently close to the identity. One corollary of this is that the multiplication operation

and can thus be applied to linear operators sufficiently close to the identity. One corollary of this is that the multiplication operation  is real analytic in local coordinates, and so every smooth Lie group is in fact a real analytic Lie group.

is real analytic in local coordinates, and so every smooth Lie group is in fact a real analytic Lie group.

It turns out that one does not need the full force of the smoothness hypothesis to obtain these conclusions. It is, for instance, a classical result that  regularity of the group operations is already enough to obtain the Baker-Campbell-Hausdorff formula. Actually, it turns out that we can weaken this a bit, and show that even

regularity of the group operations is already enough to obtain the Baker-Campbell-Hausdorff formula. Actually, it turns out that we can weaken this a bit, and show that even  regularity (i.e. that the group operations are continuously differentiable, and the derivatives are locally Lipschitz) is enough to make the classical derivation of the Baker-Campbell-Hausdorff formula work. More precisely, we have

regularity (i.e. that the group operations are continuously differentiable, and the derivatives are locally Lipschitz) is enough to make the classical derivation of the Baker-Campbell-Hausdorff formula work. More precisely, we have

Theorem 1 ( Baker-Campbell-Hausdorff formula) Let

Baker-Campbell-Hausdorff formula) Let  be a finite-dimensional vector space, and suppose one has a continuous operation

be a finite-dimensional vector space, and suppose one has a continuous operation  defined on a neighbourhood

defined on a neighbourhood  around the origin, which obeys the following three axioms:

around the origin, which obeys the following three axioms:

Then  is real analytic (and in particular, smooth) near the origin. (In particular,

is real analytic (and in particular, smooth) near the origin. (In particular,  gives a neighbourhood of the origin the structure of a local Lie group.)

gives a neighbourhood of the origin the structure of a local Lie group.)

Indeed, we will recover the Baker-Campbell-Hausdorff-Dynkin formula (after defining  appropriately) in this setting; see below the fold.

appropriately) in this setting; see below the fold.

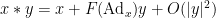

The reason that we call this a  Baker-Campbell-Hausdorff formula is that if the group operation

Baker-Campbell-Hausdorff formula is that if the group operation  has

has  regularity, and has

regularity, and has  as an identity element, then Taylor expansion already gives (2), and in exponential coordinates (which, as it turns out, can be defined without much difficulty in the

as an identity element, then Taylor expansion already gives (2), and in exponential coordinates (which, as it turns out, can be defined without much difficulty in the  category) one automatically has (3).

category) one automatically has (3).

We will record the proof of Theorem 1 below the fold; it largely follows the classical derivation of the BCH formula, but due to the low regularity one will rely on tools such as telescoping series and Riemann sums rather than on the fundamental theorem of calculus. As an application of this theorem, we can give an alternate derivation of one of the components of the solution to Hilbert’s fifth problem, namely the construction of a Lie group structure from a Gleason metric, which was covered in the previous post; we discuss this at the end of this article. With this approach, one can avoid any appeal to von Neumann’s theorem and Cartan’s theorem (discussed in this post), or the Kuranishi-Gleason extension theorem (discussed in this post).

— 1. Proof of Baker-Campbell-Hausdorff formula — We begin with some simple bounds of Lipschitz and  type on the group law

type on the group law  .

.

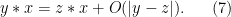

Lemma 2 (Lipschitz bounds) If  are sufficiently close to the origin, then

are sufficiently close to the origin, then

and

and

and similarly

Proof: We begin with the first estimate. If  , then

, then  is small, and (on multiplying by

is small, and (on multiplying by  ) we have

) we have  . By (2) we have

. By (2) we have

and thus

As  is small, we may invert the

is small, we may invert the  factor to obtain (4). The proof of (5) is similar.

factor to obtain (4). The proof of (5) is similar.

Now we prove (6). Write  . From (4) or (5) we have

. From (4) or (5) we have  . Since

. Since  , we have

, we have  , so by (2)

, so by (2)  , and the claim follows. The proof of (7) is similar.

, and the claim follows. The proof of (7) is similar.

Lemma 3 (Adjoint representation) For all  sufficiently close to the origin, there exists a linear transformation

sufficiently close to the origin, there exists a linear transformation  such that

such that  for all

for all  sufficiently close to the origin.

sufficiently close to the origin.

Proof: Fix  . The map

. The map  is continuous near the origin, so it will suffice to establish additivity, in the sense that

is continuous near the origin, so it will suffice to establish additivity, in the sense that

for  sufficiently close to the origin.

sufficiently close to the origin.

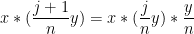

Let  be a large natural number. Then from (3) we have

be a large natural number. Then from (3) we have

where  is the product of

is the product of  copies of

copies of  . Conjugating this by

. Conjugating this by  , we see that

, we see that

But from (2) we have

and thus (by Lemma 2)

But if we split  as the product of

as the product of  and

and  and use (2), we have

and use (2), we have

Putting all this together we see that

sending  we obtain the claim.

we obtain the claim.

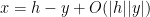

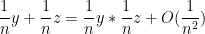

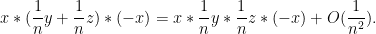

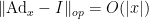

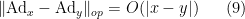

From (2) we see that

for  sufficiently small. Also from the associativity property we see that

sufficiently small. Also from the associativity property we see that

for all  sufficiently small. Combining these two properties (and using (4)) we conclude in particular that

sufficiently small. Combining these two properties (and using (4)) we conclude in particular that

for  sufficiently small. Thus we see that

sufficiently small. Thus we see that  is a continuous linear representation. In particular,

is a continuous linear representation. In particular,  is a continuous homomorphism into a linear group, and so we have the Hadamard lemma

is a continuous homomorphism into a linear group, and so we have the Hadamard lemma

where  is the linear transformation

is the linear transformation

From (8), (9), (2) we see that

for  sufficiently small, and so by the product rule we have

sufficiently small, and so by the product rule we have

Also we clearly have  for

for  small. Thus we see that

small. Thus we see that  is linear in

is linear in  , and so we have

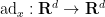

, and so we have ![\displaystyle \hbox{ad}_x y = [x,y] \displaystyle \hbox{ad}_x y = [x,y]](http://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5Cdisplaystyle++%5Chbox%7Bad%7D_x+y+%3D+%5Bx%2Cy%5D&bg=ffffff&fg=000000&s=0)

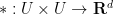

for some bilinear form ![{[,]: {\bf R}^d \rightarrow {\bf R}^d} {[,]: {\bf R}^d \rightarrow {\bf R}^d}](http://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%7B%5B%2C%5D%3A+%7B%5Cbf+R%7D%5Ed+%5Crightarrow+%7B%5Cbf+R%7D%5Ed%7D&bg=ffffff&fg=000000&s=0) .

.

One can show that this bilinear form in fact defines a Lie bracket, but for now, all we need is that it is manifestly real analytic (since all bilinear forms are polynomial and thus analytic), thus  and

and  depend analytically on

depend analytically on  .

.

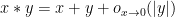

We now give an important approximation to  in the case when

in the case when  is small:

is small:

Lemma 4 For  sufficiently small, we have

sufficiently small, we have

where

Proof: If we write  , then

, then  (by (2)) and

(by (2)) and

We will shortly establish the approximation

inverting

we obtain the claim.

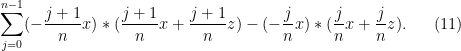

It remains to verify (10). Let  be a large natural number. We can expand the left-hand side of (10) as a telescoping series

be a large natural number. We can expand the left-hand side of (10) as a telescoping series

Using (3), the first summand can be expanded as

From (4) one has  , so by (6), (7) we can write the preceding expression as

, so by (6), (7) we can write the preceding expression as

which by definition of  can be rewritten as

can be rewritten as

From (4) one has

while from (9) one has  , hence from (2) we can rewrite (12) as

, hence from (2) we can rewrite (12) as

Inserting this back into (11), we can thus write the left-hand side of (10) as

Writing  , and then letting

, and then letting  , we conclude (from the convergence of the Riemann sum to the Riemann integral) that

, we conclude (from the convergence of the Riemann sum to the Riemann integral) that

and the claim follows.

We can then integrate this to obtain an exact formula for  :

:

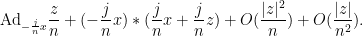

Corollary 5 (Baker-Campbell-Hausdorff-Dynkin formula) For  sufficiently small, one has

sufficiently small, one has

The right-hand side is clearly real analytic in  and

and  , and Lemma 1 follows.

, and Lemma 1 follows.

Proof: Let  be a large natural number. We can express

be a large natural number. We can express  as the telescoping sum

as the telescoping sum

From (3) followed by Lemma 4 and (8), one has

We conclude that

Sending  , so that the Riemann sum converges to a Riemann integral, we obtain the claim.

, so that the Riemann sum converges to a Riemann integral, we obtain the claim.

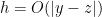

Remark 1 It seems likely that one can relax the  type condition (2) in the above arguments to the weaker

type condition (2) in the above arguments to the weaker  conditions

conditions

and

where  is bounded by

is bounded by  for some function

for some function  that goes to zero at zero, and similarly for

that goes to zero at zero, and similarly for  , as the effect of this is to replace various

, as the effect of this is to replace various  errors with errors

errors with errors  that still go to zero as

that still go to zero as  . However,

. However,  type regularity is what is provided to us by Gleason metrics, so this type of regularity suffices for applications related to Hilbert’s fifth problem.

type regularity is what is provided to us by Gleason metrics, so this type of regularity suffices for applications related to Hilbert’s fifth problem.

— 2. Building a Lie group from a Gleason metric — We can now give a slightly alternate derivation of Theorem 7 from the previous post, which asserted that every locally compact group with a Gleason metric was isomorphic to a Lie group. As in those notes, one begins by constructing the space  of one-parameter subgroups, demonstrating that it is isomorphic to a finite-dimensional vector space

of one-parameter subgroups, demonstrating that it is isomorphic to a finite-dimensional vector space  , constructing the exponential map

, constructing the exponential map  , and then showing that this map is locally a homeomorphism. Thus we can identify a neighbourhood of the identity in

, and then showing that this map is locally a homeomorphism. Thus we can identify a neighbourhood of the identity in  with a neighbourhood of the origin in

with a neighbourhood of the origin in  , thus giving a locally defined multiplication operation

, thus giving a locally defined multiplication operation  in

in  . By construction, this map is continuous and associative, and obeys the homogeneity (3) by the definition of the exponential map. Now we verify the

. By construction, this map is continuous and associative, and obeys the homogeneity (3) by the definition of the exponential map. Now we verify the  estimate (2). From Lemma 8 in the previous post, one can verify that the exponential map is bilipschitz near the origin, and the claim is now to show that

estimate (2). From Lemma 8 in the previous post, one can verify that the exponential map is bilipschitz near the origin, and the claim is now to show that

for  sufficiently close to the identity in

sufficiently close to the identity in  . By definition of

. By definition of  , it suffices to show that

, it suffices to show that

for all  ; but this follows from Lemma 8 of the previous post (and the observation, from the escape property, that

; but this follows from Lemma 8 of the previous post (and the observation, from the escape property, that  and

and  ).

).

Applying Theorem 1, we now see that  is smooth, and so the group operations are smooth near the origin. Also, for any

is smooth, and so the group operations are smooth near the origin. Also, for any  , conjugation by

, conjugation by  is an (local) outer automorphism of a neighbourhood of the identity, hence also an automorphism of

is an (local) outer automorphism of a neighbourhood of the identity, hence also an automorphism of  . Since linear maps are automatically smooth, we conclude that conjugation by

. Since linear maps are automatically smooth, we conclude that conjugation by  is smooth near the origin in exponential coordinates. From this, we can transport the smooth structure from a neighbourhood of the origin to the rest of

is smooth near the origin in exponential coordinates. From this, we can transport the smooth structure from a neighbourhood of the origin to the rest of  (using either left or right translations), and obtain a Lie group structure as required.

(using either left or right translations), and obtain a Lie group structure as required.